POLITICAL ACTIONS

South Africa United States England Europe Mexico City & Central America

This is a limited selection of my actions, including only those which I initiated on my own, or with others, or in which I took a significant leadership role.

South Africa

1962

Joined the Liberal Party in Cape Town when I was 23.

This Party was a multi-racial and non-communist political party which was against all manifestations of apartheid and which subscribed to universal suffrage. It was a fringe party without representation in Parliament. I was 25 years old when I was elected to the Activities Committee. Among other activities, we organized the protest described below.

1963

Arrested in Cape Town while picketing at a peaceful demonstration protesting the Government's banning of Peter Hujl, the leader of the Liberal Party, as a communist.

All participants in the demo were arrested. Before the trial, I left the country to attend graduate school in the United States. I was therefore guilty of contempt of court, and I was supposed to be tried for this offence if I ever returned to South Africa. However, my father used his considerable influence to have the charge against me quashed without informing me.

1963

Joined the African Resistance Movement (ARM), an underground sabotage organization in Cape Town.

The ARM was founded by disillusioned members of the Liberal Party who came to question the efficacy of non-violent strategies. The ARM's major strategy was to bomb the South African government's property in an effort to destablize the South African economy. Our assumption was that this would discourage other countries from investing in South Africa.

The ARM's policy was to avoid physically injuring or killing individuals. Ten years of incarceration was the typical sentence for those caught with a supply of weapons — even if they had not yet engaged in any sabotage.

Among other things, I recruited a surgeon to treat any ARM members who were injured when setting off bombs; mapped the terrain near my parents' house where a bombing was planned; persuaded my parents to leave their home on the evening an act of sabotage was planned so the ARM members involved could shower and change their clothes before escaping the scene.

Before the ARM was busted, I left the country to pursue my education in the United States — as I had planned to do before joining the ARM. When the police caught the man who had recruited me along with other members of the organization, they were imprisoned and tortured while awaiting trial. Meanwhile, several of the leaders managed to escape to other countries.

1987

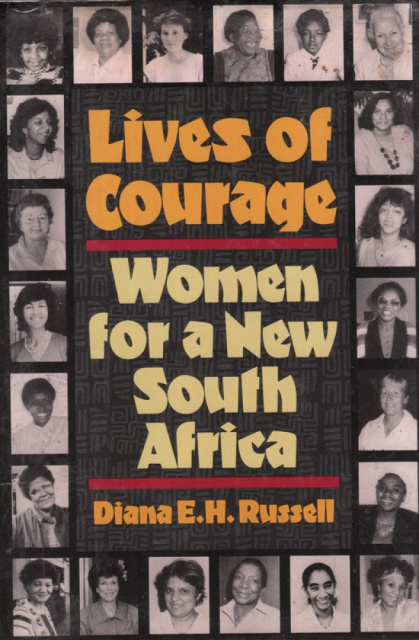

Interviewed about 50 women revolutionary activists in the liberation struggle in South Africa for a book, Lives of Courage: Women for a New South Africa.

In 1987, I travelled to Cape Town with a friend to interview women who had undertaken significant risks for the anti-Apartheid struggle. My hope was that the heroic stories of these women would humanize people that the American Government dismissed as “terrorists,” and that the book would contribute to a more progressive (or less reactionary) American policy towards the liberation movement.

Because the Government had declared a State of Emergency, our project would likely be considered illegal. The tapping of phones, arrests and detentions based on whim, confiscation of mail, etc., were considered lawful practices during the State of Emergency. We were therefore at risk of being detained or deported by the Special Branch (the so-called Security Police) if we were caught interviewing political activists — particularly those who were banned or house-arrested. A member of the Special Branch contacted me near the beginning of my research, demanding to see me. I managed to talk my way out of granting his wish — a feat that would almost certainly have been impossible if attempted by a black person.

After leaving our base in Cape Town, we travelled to Port Elizabeth, Umtata (in the Traskei), Durban, Johannesburg, then on to Zimbabwe and Zambia where the African National Congress in Exile had their headquarters — interviewing everywhere we went. My friend taped every interview, made duplicate tapes, and mailed the tapes in different mail boxes. All our tapes save those sent through the University mail system in a small town, arrived safely in the United States.

We were always anxious about being followed by members of the Special Branch, particularly because of the possibly harmful repercussions that might result for the women we had interviewed if our tapes were confiscated.

At the end of four months, we were finally able to leave South Africa. After returning home, all the tapes were transcribed, and I had the difficult job of selecting the inspiring and courageous stories of only 22 women for inclusion in the book. My publisher agreed to send about two thousand copies of Lives of Courage: Women for a New South Africa to a South African publisher for distribution in that country.

|

|

Lives of Courage:

Women for a New

South Africa book

. |

Although I had included the story of a woman who was under a banning order forbidding her to be quoted, the government did not ban the book. The only compromise made in the hope that the book would escape the banning process, was that the generous praise of Oliver Tambo, the President of the African National Conference in Exile, was not included among the endorsements printed on the back cover.

1987

Photographed about 50 women revolutionaries and activists in the liberation struggle in South Africa. Some selected by the International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa, London, England, for their documents library used by media, writers etc., 1988. Fees were paid by the media and authors to publish these photographs.

Many years later, photographs of 20 of the women whose pictures were published in my book, Lives of Courage: Women for a New South Africa, were exhibited in the Castle in Cape Town.

1993

Initiated an organization called Women United Against Incest support incest survivors who decided to participate in legal proceedings against their perpetrators.

A Supreme Court case involving Jenni Cory, 22, a deaf incest victim, whose attorney charged her older step-brother, Dr. Dieter Schmidt, 27, for having sexually abused her multiple times when she was 11 years old — was the impetus for starting Women United Against Incest. Dieter was the step-son of a famous, rich and powerful South African author called Wilbur Smith. He used all his power and resources in support of his step-son, reducing Jenni and her mother, Carol Cory, to a state of extreme poverty before the trial.

Women United Against Incest interviewed and advocated for Jenni, writing a critical letter to the Judge in the case. An attorney advised us that criticizing a judge in South Africa qualified as contempt of court. However, we refused to be intimidated about this outrageous invasion of free speech.

The day before the trial, Jenni was double-crossed by her attorney and deceived by Dieter's attorney, culminating in her being manipulated to make a settlement that she believed she had refused. The settlement, about which Jenni had inadvertently sworn not to divulge, involved her receiving a pitifully small sum of money from Wilbur Smith for therapy for the psychological damage caused by Dieter's sexually abusing her as a child.

Five members of Women United Against Incest arrived at the Supreme Court in Cape Town with our protest picket signs for what was supposed to be the first day of the trial — all wearing T-shirts on which we had painted the words “JUSTICE FOR JENNI.” By mid-night the night before, news of the last-minute settlement between the parties to the court case was not yet available to us. However, we quickly learned about it on our arrival at the court, and succeeded in confronting the Judge in person about the many injustices we had witnessed in the case, including the public revelation of his extreme bias for Dieter and against Jenni that had been documented by The Cape Times newspaper. While I went to the headquarters of The Cape Times to report the views of Women United Against Incest about the case and its outcome, including our conviction that Jenni's charges against Dieter were valid, the other members of the group went to find out how Jenni felt about what had happened.

Despite several assurances by The Cape Times journalist to whom I spoke that she had received assurance from her boss that her article reporting our views on the case would not be censored, it was! Wilbur Smith's power and willingness to use it was such that both of Cape Town's major newspapers consistently censored any statements that were sympathetic and supportive of Jenni. Instead of our views, The Cape Times published a biased and dishonest article which claimed that:

"Best-selling author Wilbur Smith and his immediate family were ecstatic yesterday when a sexual molestation damages suit against his stepson, Dr Dieter Schmidt, was finally withdrawn after a protracted and bitter legal showdown."

However, there was nothing in the settlement about Jenni withdrawing her allegations, because she never did so. The only hint of another point of view was the publication of a photograph of me outside the Supreme Court holding a large sign which read, “WILL JUSTICE TRIUMPH OVER MONEY?”, which accompanied the deceptive article. “Lone Protester,” was the misleading caption below my picture, implying that I was the only one — despite their knowledge of the involvement of Women United Against Incest in the protest. Happily, I was able to get at least one significant newspaper outside of Cape Town — where Wilbur had the most influence — to publish at least some of the truth about the case.

1993

Forcible entry organized by Rape Crisis, Cape Town, into the Attorney General's office in Cape Town to protest his decision to give bail to a dangerous rapist.

I was one of the group of about 50 women who forced our way into the Attorney Generals' office while he was meeting in private with several local journalist about his bail decision. He did his best to get us to leave and stop waving our signs around, but we refused to do so. My sign read, “IF ALL RAPISTS WERE INCARCERATED, SOUTH AFRICA WOULD BE RULED BY WOMEN!”

We were not charged with any crime when we finally left the Attorney General's office. I believe our demonstration had some influence of the Attorney General, who was making a real effort by meeting regularly with a committee of knowledgeable local women, including feminists, to try to reform the laws regarding violence against women and the sexual abuse of children.

1993

Spray painting anti-porn slogans on the windows of stores selling porn magazines in a suburb of Cape Town.

I and three other feminists participated in this illegal act. Since we were not caught, we weren't penalized for our action.

1993

Initiated first TV program in South Africa on which incest survivors talked in person about their abuse experiences — MNET.

United States

1969

|

|

Diana leaves Harvard for the Bay Area at 29.

1969

|

Initiated the first course on Women's Studies at Mills College in 1969 and co-initiated a major inWomen's Studies at Mills in 1975.

After moving from the East coast to San Francisco when I was 29 in 1968, I became a feminist.

During my first year as an Assistant Professor at Mills College in Oakland, CA, I co-taught the first course on women ever offered at the college. I subsequently continued to teach this course on my own at Mills for 22 years — after which I resigned. After a few years I introduced new courses on the Sociology of Sex Roles and Violence Against Women, and I taught other courses with a feminist perspective e.g., The Sociology of Marriage, Family and Kinship; and Human Sexuality (which was co-taught).

1971

Demonstration against an unjust rape trial, and planning an illegal destruction of property.

I participated in a demonstration outside a courthouse in San Francisco to protest the fact that the victim appeared to be on trial rather than her rapist, Mr. Plotkin.

After Mr. Plotkin was acquitted, three of us (all feminists) planned an act of sabotage involving hurling a brick through the window of Mr. Plotkin's jewelry store on Market Street in San Francisco. The following message was to be attached to the brick, reading: “As long as there's no justice for rape victims, we will have no choice but to take the law into our own hands.” However, my two female collaborators got cold feet and decided against participating. I was unwilling to do the action alone, so our plan was aborted.

1972

I started to conduct interviews with rape survivors, which culminated in my second book — The Politics of Rape (1975).

1976

The founding of Women Against Violence In Pornography and Media in San Francisco.

Inspired by the International Tribunal, a group of women organized a large-scale conference about violence against women in San Francisco in 1976.

|

|

Pornography and Pop culture conference

in San Francisco

|

A large display of pornography was arranged in the room in which a workshop on this subject was held. Horrified by the misogyny reflected in this material, I was one of several women there who decided to start the first feminist organization with a focus on combatting pornography in the United States. We named our organization, Women Against Violence In Media and Pornography ( WAVPM), and started meeting for long hours on a weekly basis.

We immediately set about organizing a protest demonstration outside the Mitchell Brothers' live porn shows in San Francisco. Next we organized a march through the porn districts of this city. Because we were so novel, our actions got great media coverage in the early years. Among other things, we invented the idea of having "Take Back the Night" marches; these marches have subsequently been organized throughout the United States, as well as in other countries. A gifted and dedicated member of WAVPM started publishing an excellent professional-looking monthly newsletter about our actions, as well as including excellent articles about pornography.

1977

Wrote and edited the text for dramatic readings based on a selection of testimonies in Crimes Against Women (referred to above) I was the narrator in a production based on Crimes Against Women which was directed by Brazillian feminist Gilda Grillo, and produced by Gloria Steinem for theNational International Women's Year Conference in Houston, Texas. (Audience: approximately 1,000).

1978

We organized a national conference in San Francisco intended to attract feminists who wanted to learn about how to build an anti-porn organization. In addition, many important substantive workshops were offered on pornography and how to combat it. Susan Brownmiller, one of the conference attendees, was greatly impressed by WAVPM and our conference. She offered to pay one of our two paid organizers to move to New York and help found a feminist anti-porn organization in that city. This resulted in the birth of what was to become the best-known feminist anti-porn group in the country: Women Against Pornography (WAP), in which Brownmiller was active for many years.

WAVPM continued it's anti-porn activities for many years. Having left this organization before it closed down as a result of the overwhelmingly libertarian culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, I do not know what year it ended. WAP and other feminist anti-porn groups outlasted WAVPM, but most of them also came to an end — defeated by the escalation and mainstreaming of pornography. Nevertheless, I and several other anti-porn feminists, continue to speak out against this misogynist propaganda and degradation of women.

1979

Prepared testimony in support of California Assemblyman Floyd Mori's bill on spousal rape, Sacramento, August 21, 1979.

1983

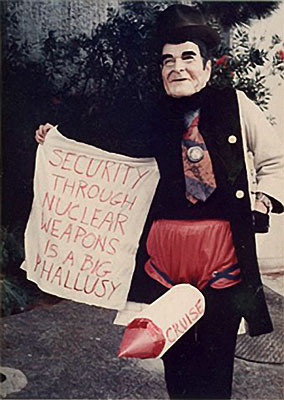

Initiated the formation of an activist organization called Feminists Anti-Nuclear Group (FANG).

|

|

Diana Russell with FANG,

Feminists Anti-Nuclear Group)

in San Francisco

|

I was greatly concerned about the failure of the peace movement to recognize the role of patriarchy in the development of nuclear arms and the terrifying danger that male leaders in the United States and the Soviet Union might use these weapons during the cold war years to engage in nuclear war. Hence, I invited other feminists to come to a meeting to discuss what we should do about this problem that threatened the survival of the entire planet. This meeting led to the formation of FANG — a small group of about eight women activists. Our major strategy was to don Reagan masks, male attire and raincoats, and then to attach large “missiles” between our legs to make the point that many male leaders appeared to think of nuclear weapons as phallic objects which they strived to make larger than those possessed by other nations, particular those they perceived as their enemies.

We would open up our raincoats and “flash” painted signs attached inside them saying things like: “Nuclear Weapons are a Big Phallacy;” and, “The MX is the Biggest Phallacy of All.” We also had cock fights with each other. Dressed in this fashion, we demonstrated in several locations, including inside the Federal Building in San Francisco. The police threw us out of this building on the grounds that we were “obscene,” despite our defence that the real obscenity is nuclear weapons and the risk of nuclear war. On another occasion the police claimed that we had to remove our masks because they were otherwise unable to identify us.

We also played the part of sexual exhibitionists flashing our phallic weapons when we participated in demonstrations and marches organized by other political groups. Anyone who looked at even one of us, immediately understood our point, and typically laughed in appreciation of the humorous way in which we conveyed our deadly serious message. In all likelihood, they also remembered our “analysis.”

1991

Arrested and incarcerated for participating in civil disobedience with two other women involving tearing up pornography in two stores.

I went to Bellingham, Washington State to testify as an expert witness in a trial of feminist activist Nikki Craft. She had spent about a month in jail for ripping four covers off a particularly sexist edition of Esquire magazine. After she agreed to pay a fine for her act of civil disobedience, I and two other local anti-porn activists also engaged in two acts of civil disobedience. First we went to a grocery store in which pornography magazines were sold, and we tore up several copies of these magazines. Our acts were witnessed by a woman cashier at the store.

Next, we entered the only porn store in Bellingham. It was owned by a pedophile some of whose acts of child sexual abuse had been exposed by Craft in her publication, The Iconoclast. A pornographic video was blaring loudly from a TV on the counter. We immediately started to tear up several porn magazines. We had been advised that if we exceeded a certain quantity of magazines, our offence would qualify as a felony; otherwise it would be a misdemeanor. We tried to gauge how much we could destroy, and stopped before we estimated that we would have committed a felony.

Craft, who remained outside the porn store, had called a radio station to inform them of what was happening. Meanwhile, the owner of the porn store locked the front door of his business so we couldn't escape, and called the police. One of the women ran toward the back door in an effort to escape. A loyal customer who tried to stop her from fleeing, ended up falling on the floor as she charged by him. He started repeatedly yelling that she had assaulted him.

Because she had been attacked by the owner during a previous demonstration, the other woman became very alarmed when we were locked in the store She kept beating on the front door as she shouted, "Let us out! Let us out!" As she continued her frantic banging, the police arrived. Unable to enter the porn store, they beat on the door, shouting "Let us in! Let us in!" By this time, a reporter from the radio station had arrived, and recorded for his live show the dramatic banging on the porn store door and the shouting by both parties. I remained motionless at the site of our crime, bewildered by the reactions of my two partners and wondering why they weren't waiting patiently to pay the price for our acts of civil disobedience.

After the owner of the porn store unlocked the front door, he pointed to the piles of torn-up porn on the floor as he told the police that we were responsible for this destruction. A policeman had also entered the back door, preventing the fleeing woman from escaping. The police then read us our rights, after which they handcuffed us and drove us to the local jail in two police cars.

After being separated from each other to make our statements to the police about our motivation for our action, the frantic woman was let out on her own recognizance. The two of us remaining, were taken to spend the night in a cell of approximately 30 sleeping inmates. The next day we were delivered to a courtroom, then released after the judge assigned us a trial date. Some time before this date, the charges against us were withdrawn because the owner of the pornstore had been arrested and charged with sexually abusing children, partly as a result of the revelations by Craft and other local anti-porn activists about the owner of the porn store.

1991

Participated in an ad hoc group of feminist anti-porn activists to protest a read-in of Playboy magazines organized by Hugh Hefner at a restaurant called Bette's Diner.

In 1991, a waitress at Bette's Diner refused to serve a male customer because he was reading Playboy. She was fired for her act of rebellion. Hefner responded by flying in a large quantity of issues of his magazine which were distributed free to all the Diner customers to read.

A crowd of about 150 women and men representing pro and con positions on pornography, were gathered outside Bette's Diner.

Our ad hoc group of about 15 feminists, most of whom were dressed in humorous anti-porn, anti-Playboy, and anti-porn-consumer costumes, participated in a boisterous protest against the read-in and the dismissal of the waitress. For example, about six of us dressed as waitresses, serving cut up, ketch-up-covered penises and balls on plates, and singing a rap song about sperm-Dick-heads which ridiculed male porn consumers. We also waived our bloody dildos and wieners at pro-porn men who were surprisingly upset about these irreverent acts. This 2-part protest received quite a bit of media coverage.

1994

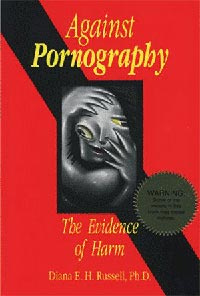

I self-published my book, Against Pornography: The Evidence of Harm.

|

|

Against Pornography:

The Evidence of Harm

published by Diana

|

After completing Against Pornography: The Evidence of Harm, I attempted to find a publisher. However, because I had included approximately 120 pornographic pictures in my book without obtaining permission from the copyright holders, I was unable to find a willing publisher because they would be at risk of being sued for breach of copyright laws. Approximately 50 printers also refused to print copies of my book, sometimes because the women employees were so upset by the material.

On finally locating a small printer to print one thousand copies of Against Pornography, I consulted several attorneys about the likelihood that I would be sued for breach of copyright. A few thought it very likely. One or two also advised me to delete my accusations against Gucionne and Flynt that they may have been responsible for the violent acts against females due to perpetrators imitating pictures in their pornographic magazines. However, I did not follow this advice as I was determined not to allow the pornographers to censor my project. Instead, I accepted the counsel of an attorney who thought a good case could be made for my being exempt from the copyright laws because I am a scholar whose aim was to educate — not sexually excite — readers, and because I was not in competition with the pornographers for their profits from selling this material.

However, this attorney warned me that were pornographers to sue me, the cost of defending myself against these rich men would likely be very high. In the event of this occurrence, I hoped I would be able to raise funds to pay my attorneys' fees.

As it turns out, I have not yet been sued for breach of copyright or for slandering Gucionne or Flynt for defamation for holding them responsible for violent acts against females due to perpetrators imitating pictures in their pornographic magazines.

1997

Two of us initiated a campaign to stop the movie: The People vs. Larry Flyntdirected by Milos Forman, from winning an Academy Award.

Feminist anti-pornography activist and researcher Wendy Stock and I organized a protest outside the theater on the day that The People vs. Larry Flynt opened in San Francisco. The movie heroized Flynt as a champion of free speech, and gave the false impression that all the women he hired — and pimped — to prostitute themselves in pornography enjoyed being required to have sex with him (i.e., being sexually harassed) as well as being photographed for pornographic purposes. Nor did the movie include information about all the feminists protests against Hustler magazine that had gone of for years. Finally, Tanya — one of Flynt's daughters — had recently charged that her father had sexually abused her as a child.

Tanya flew from Texas to speak about her father's sexual abuse at our demonstration. Wendy and I also spoke. And our action was covered in theSan Francisco Chronicle.

We also informed Gloria Steinem about our action, and were thrilled when she decided to become active in the campaign. She wrote a brilliant Op Ed article that was published in The New York Times. It had an enormous impact on their female readers, and was reprinted in other newspapers. Steinem has said that she had never before experienced the deluge of support from women for an Op Ed article she had written.

Steinem's article was published in a Hollywood publication just before the Committee voted for the winners of the Academy Awards. Although The People vs. Larry Flynt had received many awards before this point, and although many critics had mentioned it as a likely winner of an Academy Award, the movie failed to win this highly-prized recognition. Milos Forman was furious, blaming us feminists for being responsible for this outcome. I believe he was correct in his claim.

1998

Participated in feminist campaign to urge Leonardo DiCaprio to rescind his agreement to play the lead role in American Psycho based on the hardcore pornographic novel of the same name by Bret Easton Ellis.

I was among many feminists who mobilized other women and women's organizations to write letters to DiCaprio's agent, Rick Yorn, to warn him and DiCaprio of the dangers to his career and to the lives of women if he didn't change his mind about playing the lead part inAmerican Psycho.

Describing Ellis' book as “psychotic entertainment,” the Washington Feminist Faxnet described the possibility of DiCaprio's acting in this film “Outrage of the Month, if not the Year,” commenting that “if he does this he may be killing more than women on film - he'll be killing his career ”( 6/12/98).

Once again, Gloria Steinem joined this campaign. In her letter to Yorn, she started out by writing: “Now, millions of teenage (and younger) women and girls will be led by him into perhaps the most woman-loathing, sadistic, murderous, unredeemed-by-artistic-value novel published in modern times—all because Leonardo DiCaprio is starring in it.” (6/9/98).

Although neither DiCaprio or his agent acknowledged being influenced by our letter-writing campaign, DiCaprio did decide against acting in this movie. We saw this as a victory for our campaign.

2000

Co-founder of Women Against Sexual Slavery (WASS), an action group in Berkeley, California, March 2000.

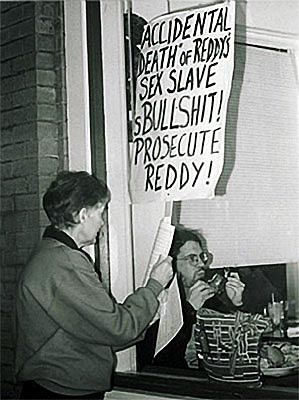

Engaged alone in a boycott of Pasand Restaurant in Berkeley, California, to educate the public and mobilize protest against Lakireddy Bali Reddy, 62 — a wealthy Indian-born Berkeley landlord — and other members of his criminal family. Their crimes included trafficking young girls from India to serve as Reddy's personal sex slaves and unpaid laborers.

|

|

Diana Russell boycotts Pasand, a

restaurant in Berkeley owned by a

sex-slaver.

|

On November 24, 1999, two of Reddy's sex slaves (17-year-old Chanti Prattipati and her 15-year-old sister) suffered from carbon monoxide poisoning from a gas leak in an apartment owned by Reddy. Chanti and her younger sister had lived there with another 20-year-old sex slave.

As a result of the intervention of a courageous woman passerby, Marcia Poole, the police arrived as Reddy, some of his family members and employees, all of whom had failed to call an ambulance or the police, were trying to escape with the two unconscious girls and a third sex slave in Reddy's truck. By January 2000, Reddy and his son Vijay were finally arrested and charged with various crimes, then released on bail.

In addition to smuggling the girls into the United States, Reddy, his two sons, his 46-year-old brother Jayaprakash Lakireddy and his 45-year-old sister-in-law Annapurna Lakireddy were also charged with tax fraud and conspiring to falsify documents in order to smuggle numerous other illegal Indian immigrants into Berkeley to work as indentured servants in Reddy's Pasand Madras Indian Cuisine Restaurant and his other family-run businesses.

On January 22, 2000, I was incensed by the revelations published in a San Francisco Chronicle article describing Lakireddy Bali Reddy's sexually abusive behavior. I decided to stand outside Reddy's Pasand Restaurant in Berkeley to hand out a flyer urging customers to boycott the restaurant. Meanwhile, I tried to find women to join me in this action. To my great disappointment, my efforts were unsuccessful that evening and for two or three months ahead. So I picketed alone (my sign read, "PROTEST SEXUAL SLAVERY BY PASAND'S OWNER! BOYCOTT PASAND!!") — urging customers, potential customers, and passersby to boycott Reddy's restaurant while handing them leaflets explaining the crimes that Reddy had been charged with perpetrating.

|

|

Diana for awhile was the lone

picketer at Pasand's Restaurant

|

I continued my solitary, almost-nightly pickets for several weeks, changing the wording on my signs from time to time, for example, to: "'ACCIDENTAL DEATH' OF REDDY'S SEX SLAVE IS BULLSHIT! PROSECUTE REDDY;" "STOP REDDY FROM GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER!!" "SUPPORT REDDY'S VICTIMS! STOP GLOBAL SEX TRADE;" "REDDY: CHILD RAPIST, PEDOPHILE, SEX SLAVER, POSSIBLE MURDERER!" I was delighted by my success in persuading many would-be customers not to dine at the Pasand. In addition, several individuals agreed not to dine there in the future.

I also picketed alone outside the Federal U.S. Court House in Oakland, California, when the early court proceedings involving Reddy occurred. Several members of a South Asian organization that had mobilized to advocate for Reddy's victims, particularly Chanti, who had died, also picketed outside the courthouse. Sadly, they would not allow me to join them because they disagreed with my focus on demanding a high sentence for Reddy.

|

|

B.J. Miller joins

Pasand boycott

|

After two or three months, my radical feminist activist friend BJ Miller, who had been out of town when I started my boycott, became my committed long-term boycott partner. Others occasionally joined us, but only one of these women became a regular picketer. We changed the wording on our signs from time to time, for example: "'ACCIDENTAL DEATH' OF REDDY'S SEX SLAVE IS BULLSHIT! PROSECUTE REDDY;" "STOP REDDY FROM GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER!!" "SUPPORT REDDY'S VICTIMS! STOP GLOBAL SEX TRADE;" "REDDY: CHILD RAPIST, PEDOPHILE, SEX SLAVER, POSSIBLE MURDERER!"

In an effort to end the boycott campaign, Reddy and some of his relatives hired an attorney to sue me on May 26, 2000. Mine was the only name they knew, so this may have been why I was singled out for their suit. One of the charges against me was that I seriously hindered Reddy's restaurant business! A pro-bono attorney agreed to defend me, and suit went on for many months, finally lapsing into oblivion. It never influenced my behavior one iota, but unfortunately it had a chilling effect on others.

|

|

Diana is joined by Marcia Poole, Grace

Christie and other women in front of

the federal courthouse in Oakland.

|

In June 2000, BJ and I decided to name our tiny group Women Against Sexual Slavery. Witness Marcia Poole joined our organization in April 2001. She focused on the court proceedings involving Reddy, and soon shared the leadership role in WASS with me. Two or three of Poole's friends also joined the organization, and finally we were able to mobilize more women to attend court proceedings.

2001

Arrested for participating in civil disobedience with more than 30 other activists protesting against the pharmaceutical companies refusal to provide affordable medication for AIDS victims in South Africa.

On March 5, 2001, 42 pharmaceutical companies took the government of South Africa to court in Pretoria because they wanted to stop South Africa importing generic AIDS medication from India, Brazil or Thailand at about 4% of the US price. The former Canadian UN Ambassador referred to the pharmacuetical industries' lawsuit as “Mass Murder.” Since the lawsuit was filed in early 1998, 400,000 South Africans had died of AIDS.

Approximately 90 protesters participating in the picket-protest rally (including me) listened to speeches by a large array of speakers. Many of us carried ready-made signs displaying a large picture of Nelson Mandela accompanied by the slogan "MANDELA SUED BY BAYER CORPORATION." Then about 30 of the protesters — including Berkeley's vice-Mayor — engaged in civil disobedience by sitting in front of the gate of Bayer Corporation (one of the pharmaceutical companies involved in the lawsuit) in Berkeley, California, singing protest songs. The police arrested two of us at a time, recorded our names and addresses and had us finger printed, then accompanied us out of Bayer's property, and released us. It was all very genteel. No handcuffs were used, and everyone behaved politiely to everyone else.

Those of us who had engaged in civil disobedience were expecting to have to pay a fine, but in the end all the charges were dropped.

I was struck by the dramatic contrast between the large number of protestors who were willing to be arrested for this cause in faraway South Africa, compared to the virtual non-existance of individuals willing to protest sexual slavery of underage girls that had continued for about 15 years under our noses and the nosed of the Berkeley police.

2002

Initiated a feminist protest outside the new Hustler Club in San Francisco on their opening night, resulting in my being physically assaulted by a man who was outraged by the sign I displayed.

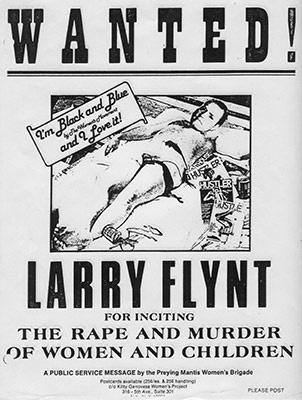

|

|

Poster from a demonstration

against Larry Flynt

|

On February 20, Larry Flynt's new Hustler Club in North Beach's sleazy porn district attracted a great deal of public and media attention. A long line of predominantly (95%) men kept growing as they waited to be admitted to the celebration party, and guests like Mayor Willie Brown, Francis Coppola, and what the San Francisco Examiner referred to as "other noted Bay Area icons," revealed how mainstream Flynt and the hard-core porn he produces have become in San Francisco.

Flynt advertized this event all over the city with a full-page color photo of two naked blond, blue-eyed young girls who appeared to be no older than 14 years of age. The picture was cropped a few inches below their waists with their breasts mostly hidden by text. Although spokesmen for the club maintained that the girls were of legal age, they were obviously chosen to appeal to men who are turned on by underage girls. Hence, we had made a sign displaying a huge blow-up of the child porn ad, and a large vinyl sign supported by wooden slats on either side, that read: "HUSTLER CLUB FOR MEN WHO NEED CHILD PORN AND ABUSE TO GET IT UP!" It was illustrated by two limp penises.

I and other members of a small group of feminists calling ourselves Women Against Pornography, carried signs or propped them up on the sidewalk in the case of the two very large ones. As I stood outside the door of the club behind the limp penises sign, a raging man, who looked to be in his 50s, charged into it, apparently intent on destroying it. Attacking the sign entailed attacking me at the same time. I fought back, but was unable to break loose. After what seemed like a long physical struggle, three male bystanders managed to break my assailant's ferocious grip on me. My magnanimous rescuers then sent him on his way without asking me if I wanted him arrested.

Many journalists, and cameramen were milling around, and although at least three newspapers quoted my views about Flynt and his club, none thought the attack on me worthy of mention. Imagine if, instead of an attack on a feminist protester, this had been an assault on a person of color who was demonstrating outside a racist organization. Is it conceivable that such an attack would have been totally ignored by the media? Would the rescuers have released the assailants? Would the incident have been erased from public record? No way!

Yet after more than three decades of women's struggle against sexism and violence against women, this example of a violent sexist reaction to a woman protester was treated as nothing more than ho-hum.

October 2003

Initiated the formation of an ad-hoc San Francisco Bay Area action group called Women Against Arnold For Governor (WAAG), advocating a “No” vote on the recall of Governor Gray Davis, and an even bigger “No” vote for Arnold Schwarzenegger as Governor.

Less than a week before the recall election in California, The Los Angeles Times' published a sensational and well-documented expose about Schwarzenegger's predatory and criminal behavior toward eight women. In response, I hastily organized the first WAAG demonstration outside the offices of the San Francisco Chronicle at noon on October 3, and a second one outside the Oakland Tribune at noon on October 6 — the day before the election. I chose these locations on the assumption that this would ensure that at least these two newspapers would cover our critiques of the candidacy for Governor of a sexual pedator who gets his jollies by groping, propositioning, sexually harassing, and sexually assaulting women.

At the first demonstation we picketed for about two hours with an assortment of hand-painted posters with slogans like, “GROUP SEX? MY FOOT! IT'S MORE LIKE RAPE IN MY BOOK,” “WOMEN AGAINST ARNOLD FOR GOVERNOR!” “TERMINATE ARNOLD! SEXUAL ASSAULT IS NOT "PLAYFUL,” “IF SHRIVER WAS RAPED, ARNOLD ‘WOULD LEAVE ME BECAUSE I'D BE DAMAGED GOODS.’” Huge blow ups of two photo from Hustler magazine displayed a man shoving a woman's head into a toilet bowl, then the woman gasping for air accompanied by the statement: “THIS IS WHAT ARNOLD WOULD LIKE TO DO TO WOMEN!.”

Buried on page 11 of the San Francisco Chronicle was a poor photograph of aCode Pink demonstration with two 5-line columns of text below the heading: “Women protest against Schwarzenegger.” The unnamed reporter mistakenly identified both demonstrations on October 3 as having been organized byWAAG. The name Code Pink was never mentioned. After correctly noting that our demonstrations were against Schwarzenegger for governor, the reporter completed the following meager text:

“Allegations of sexual harassment have rocked his campaign, while past references to women as ‘chicks’ and his treatment of Arianna Huffington at a debate have drawn criticism from women.”

That was it! This is what WAAG's press release was reduced to. No reporter even stepped out of the Chronicle's building to interview us, or to cover the lively Code Pink demonstration.

Many Code Pink protestors joined WAAG's demonstration outside the Oakland Tribune, bringing additional signs, such as “SEXUAL HARASSMENT IS ACRIME,” “STOP THE BUSH OCCUPATION OF CALIFORNIA,” “TERMINATE SEXISM!” After a while we left our location and marched around a busy area of Oakland. However, despite being interviewed by a Tribune reporter, this newspaper did not cover our demonstration at their front door. Later I was told that this newspaper had a policy against publishing an article that was critical of only one candidate on election day. Although we we interviewed this time by the Chronicle, this paper also did not cover our colorful action, despite this being the only demonstration against Arnold for Governor in Oakland.

2010 - Now

Board member of AntiPornography.org, a nonprofit organization that prevents and combats the devastating harms of pornography, prostitution, and sex trafficking, as well as all other forms of sexual exploitation, by engaging in public education and advocacy.

2010

Board of Advisors to Take Back the Night Foundation, April 2010.

England

Anti-Rape Protest

1974

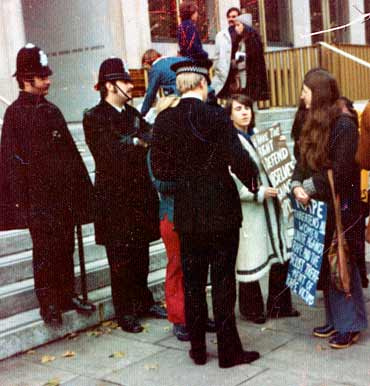

Arrested for participating in civil disobedience outside the American Embassy in London, England, to protest the 20-year sentence given to a rape survivor for killing one of her rapists.

|

|

Policemen warning protesters to disperse or

be arrested (1974)

Garcia support rally in London. 1974

|

I was in London when Inez Garcia was convicted in California of first degree murder for shooting one of her rapists. Because of the outrageously severe 20-year sentence she received for this offence, U.S. feminists stormed the court. I and an American feminist organized a demonstration outside the American Embassy in London to protest Garcia's long sentence. Of the approximately 40 women who participated, six of us refused to disperse for blocking the sidewalk when ordered to do so by the police. We were subsequently arrested by the police and held in prison for a few hours before being charged with obstruction and refusal to obey orders.

Before being released, we were told that we would have to appear in court for our trial. A feminist barrister volunteered to defend us. The case culminated in our receiving small fines.

Europe

1974

Initiated the first and only International Tribunal on Crimes Against Womenwhen I was 34 years old.

|

|

International feminist camp at Fémo, Denmark.

1974

|

I attended a 10-day international feminist camp at Fémo, which was situated on a small island in Denmark. Approximately 200 feminists — mostly from Western Europe and the United States — had gathered there every year for a number of years. Some of us initiated workshops for women who wanted to participate in this activity. I attended a workshop on ideas about international feminist actions that would provide feminist alternatives to the United Nations-initiated Conference in Mexico City in 1975 in which representatives of all the patriarchal governments in the world would be engaged in developing a plan of action for the improvement of womens' status.

It was at this workshop that I came up with the idea of organizing anInternational Tribunal on Crimes Against Women at which personal testimony would be given on many of the “crimes” that discriminate against, exploit and oppress women. Since no one else at Fémo shared my enthusiasm for my idea about such a tribunal, I set about organizing it on my own. I started by initiating a workshop on the tribunal at a forthcoming feminist conference in Frankfurt, Germany.

This time I succeeded in interesting a few women at the workshop in my idea of an international feminist speak out. Some of these women volunteered to organize committees in the countries where they were living, the purpose of which would be to decide on which crimes against women the committee members wished to provide testimony on at the International Tribunal, and to select women survivors of these crimes who would be willing to testify about their experiences to the women attending this event.

|

|

Nicole Van de Ven, Lydia Horton and Diana

Russell, Major organizers of the International

Tribunal on Crimes Against Women" (1974)

|

I was one of a handful of women who agreed to be on the co-ordinating committee to make decisions about where the Tribunal would be held, how to handle the international media, and how to conduct the event.

1976

Instead of taking place in 1975, as we had intended, the International Tribunal on Crimes Against Womentook place in Brussels, Belgium, during four days in March 1976. Approximately 2,000 women attended from 40 countries. Simultaneous translations were conducted by volunteers in five languages. The Tribunal was a resounding success. Simone de Beauvoir described it as “the beginning of the radical decolonization of women.”

|

|

2,000 participants at International Tribunal on

Crimes Against Women. 1974

|

The Tribunal inspired many of the feminists participants to create organizations and engage in actions in their home countries that they had learned about at this massive international consciousness-raiser. Tribunals were also held in New York. Some people believe that theTribunal was the beginning of the movement against violence against women in Western Europe. For example, numerous battered women shelters were started by feminists in Germany after hearing the British women testify about the battering they had been subjected to by their husbands, or former husbands, and their escape to shelters.

|

|

Lesbian demonstrators take over the stage, to protest being

scheduled to testify on last day

|

In addition, the Tribunal model based on personal testimony has become a popular and effective method of public education and the mobilization of women to try to combat the crimes against women about which the testimony is focused, e.g., in Geneva Switzerland, [others to be mentioned]. More recently, several tribunals have been organized in third world countries — particularly in Asia.

These amazing achievements culminated from my inspirational dream that I had in an all-women, all-feminist environment in 1974. Many other radical feminist actions also incubated at Fémo, revealing the tremendous empowerment and radicalization of women that can occur in all-women environments.

I initiated the International Feminist Network (IFN) at the end of theInternational Tribunal. The purpose of the IFN was to mobilize international feminist letter-writing campaigns requested by feminists in different countries who believed that a barrage of letters from their international sisters would serve to shame those responsible for whatever anti-women actions concerned them.

Women in an organization called ISIS in Carouge, Switzerland, volunteered to organize and run the IFN. They diligently fulfilled this responsibility for many years, often publishing articles about these issues in their monthly magazine (also called ISIS), which was distributed to women in many nations. At some point, a group of women in Kenya took on this responsibility — which they still have to this day.

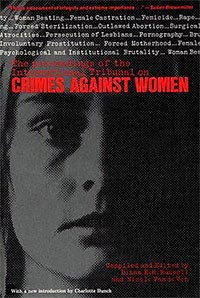

|

|

Crimes Against Women:

The Proceedings of the

International Tribunal book

|

A book entitled, Crimes Against Women: The Proceedings of the International Tribunal, was published in 1976. Belgian feminist Nicole van de Ven was responsible for translating all of the testimonies into English or arranging for others to translate them, whereas I authored all but one of the authored chapters and edited all of the testimony presented at the International Tribunal.

Mexico City and Central America

1975

Another U.S. feminist (Judy Friedlander) and I organized an international speakout at the United Nations'-sponsored “People's Conference” in Mexico City during the International Year of the Woman.

The purpose of this event was to test the Tribunal model as well as to publicize the forthcoming International Tribunal, and to raise the awareness of those present about the crimes against women about which women from many countries testified.

Co-organizer of two sessions entitled The International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women. International Women's Year Tribune. Mexico City, Mexico, June-July, 1975.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For more photos of Diana's activism, please visit her Activism Photos.

Top