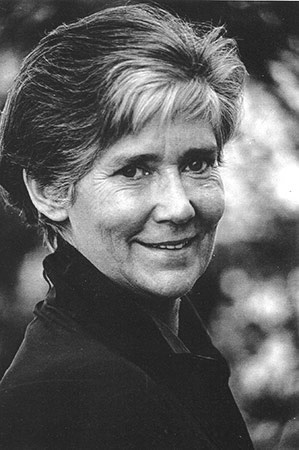

BIOGRAPHY

|

I was born in 1938 and raised in Cape Town, South Africa. I am the fourth of six children, preceding my twin brother David by only thirty minutes. My South-African-born father became a Member of Parliament in 1945, and my British mother, who traveled to South Africa to teach elocution and drama, became a full-time mother and housewife on marrying my father.

On graduating with a B.A. from the University of Cape Town, I left South Africa when I was 19 years old, arriving in England in early 1957. After working there for two years, I began training for a career in social work by enrolling in a Postgraduate Diploma in Social Science and Administration at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

|

In addition to passing this Diploma with Distinction, I was awarded a prize as the best student in this program in 1961. Thrilled by my unexpected achievement, I decided to forgo becoming a social worker and instead applied to Ph.D. programs in the United States, hoping to study social psychology. While visiting my family in 1963, I joined the Liberal Party that Alan Paton, the renowned author of Cry the Beloved Country (1948), had founded in 1953.

After participating in a peaceful protest in Cape Town in 1963 about the banning of our Party's leader, I and the other protesters were arrested. Disenchanted with peaceful protests, I made the most momentous decision I'd ever before made to join an underground revolutionary organization called The African Resistance Movement (ARM). Most of the other participants in the ARM were similarly disillusioned members of the Liberal Party, who had, like me, come to the conclusion that above-ground non-violent strategies would be futile against the brutal, white Afrikaner police state.

Sabotage involving the bombing of government property was the primary strategy employed by the ARM, the goal of which was to discourage foreign investments in South Africa. The ARM firmly rejected all forms of violence against individuals. When members of the security police discovered bombs hidden in the homes or offices of would-be saboteurs, these rebels would typically be sentenced to about 10 years in prison -- even if they hadn't yet managed to deploy their weapons.

Although I was only a peripheral member of the ARM because of my plans to attend graduate school in the United States, I nevertheless believed that my membership and activities in this organization put me at risk of 10 years of incarceration were I to be apprehended. Fortunately for me, I was spared this fate.

I left for the United States and started my interdisciplinery graduate studies at Harvard University in the Fall of 1963 when I was 23. While there, my interest shifted to sociology and the study of revolution. On completing my courses at Harvard, I obtained a position as a Research Associate at Princeton University where I worked on my dissertation on this topic.

In 1968, I married an American psychologist who taught and conducted his research at the University of California in San Francisco. Forced to obtain a position within a commutable distance, I accepted a position in 1969 as an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Mills College, a private women's school in Oakland, California.

During my first year at Mills College, I co-taught the first course on women that had ever been offered there, and one of the first courses on women taught in the United States. During the 22 years that I remained at Mills, ending up as a Full Professor of Sociology, I was able to play a major role in introducing feminism to this heretofore sexist college by teaching additional courses on women and sexism, as well as by co-initiating and developing a major in women's studies.

My book, The Politics of Rape, published in 1975, was among the first feminist analyses suggesting a causal relationship between accepted notions of masculinity and the perpetration of rape. My theory that rape is an act of conformity to ideals of masculinity -- rather than a deviant act -- contributed to revolutionizing society's understanding of these traumatic, misogynist crimes.

In 1977, I started designing a scientific study of the prevalence and effects of rape and incestuous abuse of females based on interviews with 930 women in San Francisco. I described and analyzed the findings of this survey in a series of books including Rape in Marriage (1982), Sexual Exploitation: Rape, Child Sexual Abuse, and Workplace Harassment (1984), and The Secret Trauma: Incest in the Lives of Girls and Women (1986). The Secret Trauma, the first scientific study of incestuous abuse ever conducted, was the co-recipient of the prestigious C. Wright Mills Award in 1986. My findings on the prevalence of rape, of which the vast majority had never been reported, was by far the highest ever found before or since.

Commenting on my survey, David Finkelhor, the foremost expert on child sexual abuse, stated:

"Russell's survey on sexual assault is the best that's been done.... She

convincingly shows that sexual exploitation occurs in mammoth

proportions, and she presents the first hard data to answer dozens of questions.

This is a giant step forward in our accumulation of knowledge about rape,

sexual abuse, and sexual harassment."

Redefining and politicizing Carol Orlock's term "femicide" in 1976 to refer to the killing of females by males because they are female, I later co-edited an anthology titled Femicide: The Politics of Woman Killing in 1992. This volume inspired well-known Mexican feminist anthropologist and former Congresswoman Marcela Lagarde to initiate a movement against femicide in Mexico. The mobilization of feminists to combat this widespread misogynist crime then spread to Guatemala, Costa Rica, Chile, El Salvador, and several other Latin American countries.

Turning to the critical issue of pornography, I was a founding member of Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media (WAVPM) in 1977 -- the first feminist anti-pornography organization in the United States and internationally. I was also among the first to publish a feminist analysis of pornography in 1977 ("On pornography," Chrysalis, No. 4, pp. 11-15). In 1993, I edited an anthology on pornography titled, Making Violence Sexy: Feminist Views on Pornography. One year later in 1994, I decided to risk being sued for breach of copyright laws for including over 100 pornographic pictures in my book, Against Pornography: The Evidence of Harm. Refusing to seek permission to publish these woman-hating masturbatory photos, I provided scientific evidence of the causal relationship between the exposure of males to pornography and an increase in their pro-rape attitudes and behavior.

In 1987, I traveled to my native South Africa to conduct interviews with revolutionary women activists in the anti-apartheid liberation struggle, which culminated in my book titled Lives of Courage: Women for a New South Africa (1989). I also published two other books and several articles on sexual abuse and violence against girls and women there.

Aside from being one of the pioneers among second wave feminists to offer a feminist analysis of rape, my books have also covered the widest range in types of violence against women and girls -- including different kinds of rape (e.g., rape by husbands, lovers, relatives, strangers and acquaintances), woman beating/battering, femicide, the torture of women, incestuous and extrafamilial child sexual abuse, and pornographic sexual violence. In addition, I have published a large number of articles and chapters about female victims and survivors of sexual violence in other countries, especially in South Africa. According to rape researcher Timothy Beneke,

"Russell is one of the world's most prolific social scientists writing about violence against women."

Aside from my 40 years of research on male sexual violence and all levels of abuse of females, I have a long history of feminist activism in the United States, South Africa, and several other countries. In 1974, I succeeded in mobilizing other feminists to join me in organizing the first feminist International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women. This four-day global women's speak-out denouncing all forms of patriarchal oppression, discrimination, and violations of women and girls, occurred in Brussels, Belgium, in 1976. Attended by about 2,000 women from 40 countries, Simone de Beauvoir declared in her introductory speech to the Tribunal:

"I salute the International Tribunal as the beginning of the radical decolonization of women."

Belgian feminist Nicole Van de Ven and I subsequently documented and analyzed this unique, herstoric global protest in a book titled, Crimes Against Women: The Proceedings of the International Tribunal (1976).

I also started the Feminists' Anti-Nuclear Group (FANG) in 1983 in response to the failure of the peace movement to recognize the role of patriarchy in the development of nuclear arms. My concern also culminated in the publication of my book, Exposing Nuclear Phallacies (1989), designated an Outstanding Book on human rights in the United States by the Gustavus Myers Center in 1990.

I have been arrested five times -- twice in other countries -- and sued once in Berkeley, CA.

After focusing for 40 years on conducting research, writing and publishing books and articles, public speaking, and political activism to combat male sexual violence against females, I recently shifted my attention to writing my memoirs. My first volume will reveal why I have devoted my adult life to tearing down the veils of secrecy about the mammoth dimensions of male violence and sexual abuse of females, and the devastating consequences of these acts.

Diana E. H. Russell, Ph.D.

[*I'm indebted to Alix Johnson for editing this biography]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Diana passed away on July 28, 2020. Please see her obituary here on this website.